The Germ

I remember once reading in a book called “The Coming of Bill” by P.G. Wodehouse, the funniest, most naïve description of a “germ” as imagined by a child, William Bannister Winfield. Following is the excerpt:

The door opened slowly. A head insinuated itself into the room, furtively, as if uncertain of its welcome. The door continued to open and Steve slipped in.

….The child’s mouth opened. Steve eyed him, fascinated. No bird, encountering a snake, was ever so incapable of movement as he.

“Are you a germ?” inquired William Bannister.

“Why, for the love of Mike,” said Steve, “don’t you know me, kid? I’m not a porch-climber. Don’t you remember Steve who used to raise Hades with you at the studio? Darn it, I’m your godfather! I’m Steve!”

William Bannister sat up, partially reassured.

“What’s Steve?” he inquired.

“I’m Steve.”

“Why?”

“How do you mean–why?”

The large eyes inspected him gravely.

“I thought you were a germ.”

“A what?”

“They get at you and hurt you.”

“Are you scared of germs?”

The White Hope nodded gravely.

“I have to be sterilized because of them. Are you sterilized?”

I remember reading this amusing piece of writing again and again and laughing at it. I read the book sometime in the early 2000s – of course I knew what germs and microbes were by then, they were not large ugly men who sneak into your room in the middle of the night like William Bannister thought, they were tiny invisible creatures that would cause your stomach to ache and throat to itch, but as soon as the doctor gave me an “antibiotic”, they would vanish (the pills were scary to swallow, but they worked wonders). P.G Wodehouse wrote this book in 1919 – almost a decade before Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming. And when Fleming won the Nobel Prize for it in 1945, he stated – “There is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself, and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant.” It was almost as if the Staphylococci heard him, and the first penicillin-resistant strains were found in the same year, shortly after penicillin was mass produced and prescribed to millions of people, from World War wounds to STDs to sore throats.

Image Source: WIFSS, UCDAVIS

So how did the germs know to resist? They aren’t humans, they don’t know to fight back, they’re merely one single cell. Well, just like any other living thing, they know to survive – they know to do anything it takes to live. Bacteria have far shorter reproductive times than most other living beings (the fastest being within 20 minutes) – this, believe it or not, gives them a great advantage – the advantage of rapid evolution. They don’t have to wait for years to evolve, only hours. When something doesn’t kill them, it empowers them. Their genetic system learns to block out the antibiotics that were developed to kill them, and this happens fast! That’s the reason an unfinished course of antibiotics leaves some bacteria alive to morph into mutants. Another amazing biological feature here is called ‘horizontal gene transfer’, a method by which bacteria can pass on these newly acquired resistance genes to other neighboring bacteria and create a whole colony of bacteria that are now resistant to your magical antibiotic.

How Our Culture Feeds Bacterial Cultures

Another book that was not only a page turner when I was a teenager, but also turned my life around and made me the biologist I am today was written by Robin Cook. It was a medical thriller called “Critical” and the main unicellular protagonist was MRSA (pronounced ‘mersa’) – Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. I was so enthralled by the book when I was an undergrad, that I decided to do a small project on it with a classmate. We applied for its publication at the International Symposium of Emerging Areas in Biosciences and Bioengineering in 2009 at a premier engineering institute in India and to our thrill, were accepted to go put up a poster on MRSA there. So, we did. One half of our poster explained the project, methods, and findings. The other half listed all the ways in which we can prevent a MRSA infection, and any infection in general. The first item on the list was “Wash hands thoroughly” (with a small picture of a pair of hands under a running tap with soap foam on them). Every single person who walked by our poster smiled, grinned, rolled their eyes, or even openly sniggered at that. We went back feeling naïve and un-scientific and dumb (MRSA – 1; Me – 0).

Today when I look at where we are, if anything, I would go back and put that line in larger, bolder letters. But even so, we found out in 2016 from an FDA ban of anti-bacterial hand soaps, that washing hands has been a poorly informed phenomenon in itself. Antibiotics like benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride and chloroxylenol (PCMX) that were ingredients inn these soaps were found to create drug resistant bacteria on skin.

Ever since humans started living in isolated civilized colonies, bugs (read as microbes here) were a problem, then we figured out antibiotics in the 1900s and oh saved so many lives! And then came the problems of overuse and unnecessary use. Antibiotics were prescribed for every mild discomfort experienced by Fleming’s “ignorant man”, without first understanding everything about those small pills from heaven. Even today I have people around me suggesting I take Amoxicillin if I sneeze a few times. And I get a “rolling of eyes” when I say that that’s an antibiotic and for all I know I could have a common cold virus (MRSA – 2; Me – Still 0).

It was estimated in the 2016 AMR Review that globally at least 700,000 people die annually due to drug resistant bacteria, and the study projected 1 million deaths by 2050. No prize for guessing who’s responsible here. We’re Professor Utonium (or Mojo Jojo as we find out later), we’re Victor Frankenstein. The only difference being, we didn’t do that by accident, we did it by sheer dumb ignorance.

A PEW report from 2016 showed that 30% of antibiotic prescriptions written annually are unnecessary. Translated into numbers, that’s 47 million unnecessary prescriptions every year. The common cold gets about 8 million unwanted prescriptions each year (and this is not by friends, it’s by practicing healthcare professionals). Unfortunately, in a world so consumed by the idea that healthcare advancements can cure almost anything, we have people wanting quick fixes, and healthcare professionals lending to this, making the understanding of where to use antibiotics not as widespread as we would imagine. The notion that a sinus headache or a viral attack takes a while to abate is somehow not very appealing. Soup and hot tea that our grandmothers advised us to drink when we get a sore throat is not what we want anymore, we want a fix right here right now. This shoot-first-ask-questions-later policy has brought us to a world where if we look closely under the microscope in a lab, we may see Staph aureus with a cape or a light saber.

Another huge consumer of antibiotics which bites us in the behind is the industrial animal farming sector. As Michael Pollan explains in his book “The Omnivore’s Dilemma”, animals are crowded together in feedlots and fed highly concentrated ration to maximize meat yield, and that cannot possibly be sustainable without the use of a substantial amount of antibiotics. These antibiotics fed to cows, sheep, pigs, and chicken, contaminate the surrounding soil, water and environment, and are responsible for drug resistant microbes to be transmitted to human beings living in the area. The CDC found that about 1 in 5 resistant infections are caused by germs from food and animals. Another study published in 2013 confirmed that people living near pig farms are 30% more likely to encounter MRSA infections.

Image Source: DailyHealthPost.com

Big Pharma?

The late 1900s was the Golden Age of Antibiotics. Briefly coming back to the Penicillin story, Nathan Florey was a scientist at Oxford University, and was the mastermind behind figuring out mass production of the antibiotic. However, upon the advice of the Head of the Medical Research Council, Sir Henry Dayle that it is unethical to patent a medical discovery, Florey didn’t file rights to it, and Britain had to pay the price for 25 years to the US Patent on Penicillin.

Today’s pharmaceutical industry works on incentives. So much so that what was once the most lucrative field in medicine has been deserted today. According to most recent research, only 12 antibiotics have been approved for the past decade and a half, since 2000. The study states “From a business standpoint, standard drug reimbursement, which links return on investment to the volume of drug sold, simply doesn’t work for antibiotics.” The recent AMR review revealed that less than 5% of venture capital investment on pharma R&D between 2003 and 2013 was for antimicrobial development. This comes at the time when pharmaceutical giants are pulling away from the antimicrobial front. Novartis being the most recent, follows Astrazeneca, Sanofi, and Allergan; leaving Merck, Roche, GSK, and Pfizer the only ones with active antimicrobial research.

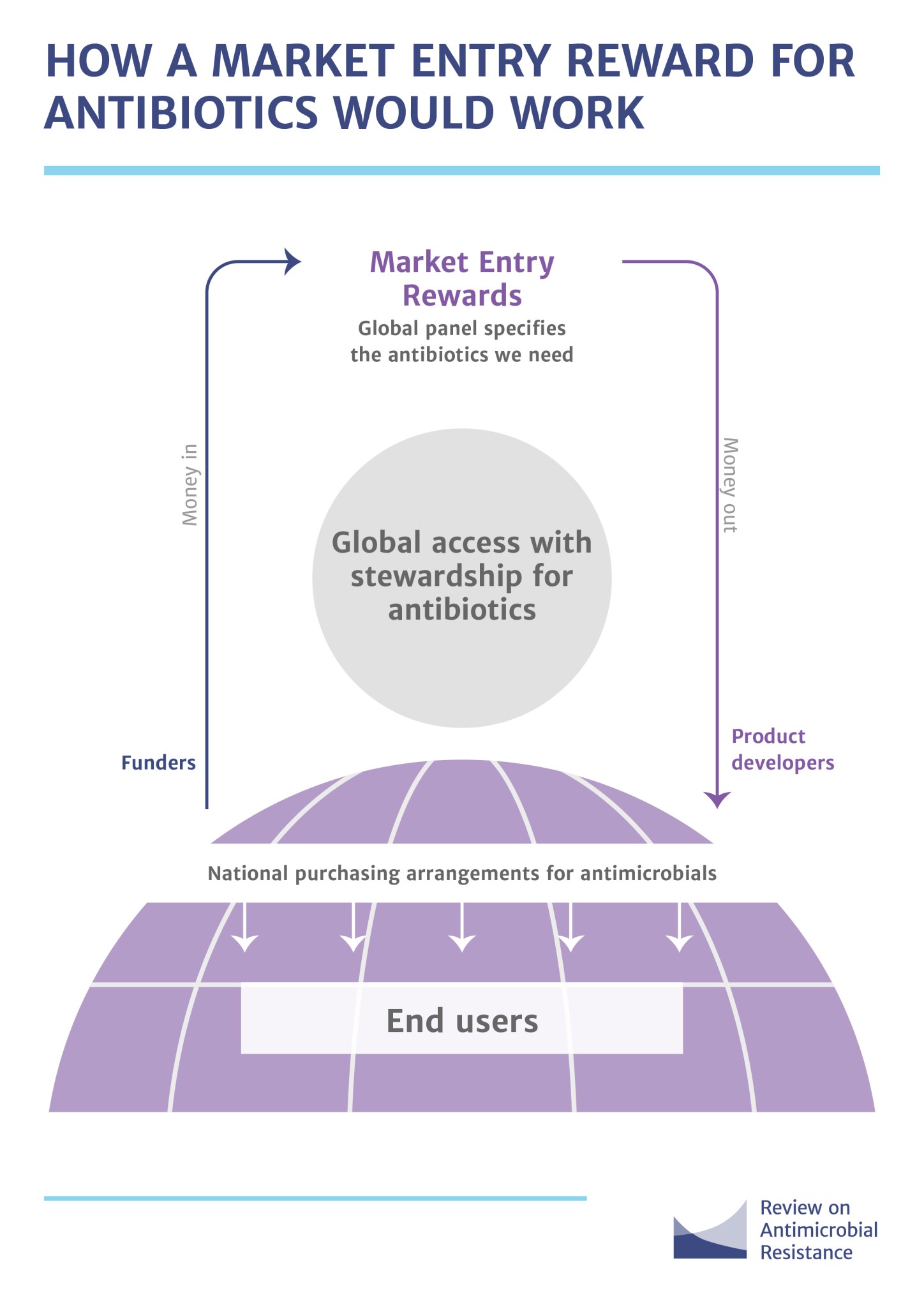

For the R&D sector, governments everywhere are trying to find more incentives to feed drug resistant microbe research. The European Joint Programming Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance, the Innovative Medicine Initiative’s (IMI) New Drugs for Bad Bugs program, the Global Antibiotics Research and Development Partnership, Novo Holdings’ REPAIR Impact Fund and the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) initiative will collectively inject over $1 billion between 2014 and 2021 (Nature, 2018). As for the market incentive, the ‘market entry reward’ or MER, is one of the most promising ideas on the table. The European Union’s DRIVE‐AB (Driving Reinvestment in R&D and Responsible Antibiotic Use) is set to redefine MER, and estimates value between $750 million and $2,000 million, paid out in installments over five years.

Image Source: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance

Alternatives and Our Involvement

Antibiotics are currently the most preferred methods of combating microbial infections, easily available, and have the fastest response times. When they pose a threat to us, people often look to the FDA for answers and regulations. When it comes to taking something out of the market, FDA’s role is cut-throat, but when we are dealing with approvals, FDA’s involvement is limited to efficacy of said drug. It is the users, the doctors, and the manufacturers, that have to up their game and strive to be more well informed of what they consume. In an earlier post about GMOs, I spoke about the labeling scenario to give consumers full transparency. It would be worth labeling the antimicrobials more optimally too.

Image Source: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance

Diagnosis of bacterial infections plays a major role in this whole melee. Aberrant diagnosis is the cause of many of the issues I have covered in this article. A wrong prescription stems primarily from the lack of efficient methods to diagnose infectious diseases early on. For all the pharma giants that are leaving this field, there are smaller ones with diagnostic kits cropping up everywhere, and they are a welcome gust of fresh air.

What if we didn’t have to use antibiotics in the first place? Could we use something totally different and circumvent this problem of multi-drug resistant microbes? Can bacteriophages solve the problem? Bacteriophages (or just phages) are anti-bacterial viruses that selectively kill only certain types of bacteria. This makes them an interesting and even a potentially great alternative to chemical compounds, but also makes it very difficult to design and use them effectively for infections. They are immunogenic, they are cleared by the body much faster than antibiotics, and they can also be inefficient against multi-bacterial strain infections such as UTI or systemic sepsis.

However, these bacteriophages can be put to better use for the rapid and safe diagnosis of blood-borne pathogen infections, which opens up a whole new world of possibilities.

Read my patent on this technology here.

While the world scrambles to provide monetary incentives because bacterial infections and antibiotic use are not as lucrative to the pharm biz as cancer or cardiac disease are, let’s take some precautions ourselves. Let’s wash our hands (just plain simple soap is good). Let’s not take antibiotics until we’re sure we need them. Multi-drug resistant bacteria infections are only a trip to a public pool or an unfinished course of antibiotics away. Let’s remember to be wary of germs and question them like smart little William Bannister Winfield did.

Nice. The analogy is superb

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. Unfortunately , history shows can that humangs are always about 2 things 1. Immediacy of pleasure/results /relief . 2. The bigger issue – money prioritised over everything else. Tough combination to beat !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an amazing read Subha. Loved the flow of the article and the holistic presentation of the topic. Great job! Keep going!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent and spot on. Somehow William Bannister seems prophetic at the end of it all …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article! Sharing this one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So well written that I felt compelled to wash my hands with mild soap before typing this comment to keep it clean. 😉

I am definitely sharing this to spread awareness into the use of antibiotics and the dangers of improper and over usage.

I see two potential scientific advances in fighting harmful bacteria: 1) Faster and accurate diagnosis of bacterial infections and 2) Inventing antibiotics targeting specific harmful bacteria strains and eliminating them fully. In the mean time, as stated well in the article, if we can spread the awareness of washing hands and avoiding the purchase of meat produce that may have been treated with antibiotics, we could go a long way.

LikeLiked by 1 person